As Texas grapples with a growing mental health crisis, Boerne police and the sheriff ’s office are turning to mental health officers to support the community’s needs.

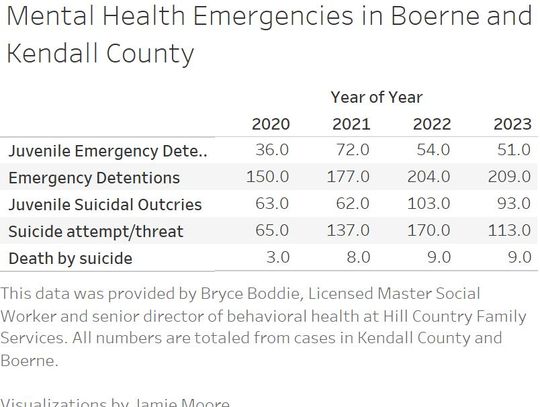

Between the Kendall County Sheriff ’s Office and Boerne police, 209 emergency detentions from crisis calls were reported in 2023, a 39% increase from 2020, according to Bryce Boddie, a licensed master social worker and senior director of behavioral health at Hill Country Family Services.

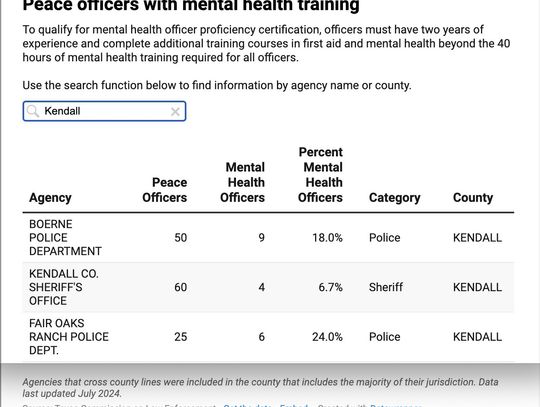

To address the growing mental health challenges, the Boerne Police Department and the sheriff ’s office each have hired and trained two designated mental health officers, with Boerne P.D. in the process of hiring a third.

Boddie was hired through a grant from Methodist Healthcare Ministries to assist Kendall County mental health officers by initially conducting clinical assessments for individuals working with the mental health officers.

“Mental health doesn’t care whether we address it or not, it’s going to exist as a problem,” Boddie said. “Whether we do something for it or just forget about it, it’s a problem.

“And when we decide to all kind of aim our arrows in the same direction and address it, we’ll be better off for that,” Boddie said.

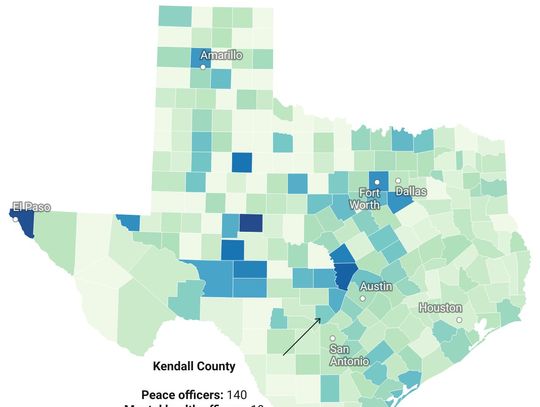

Kendall County has felt the impact of the mental health crisis. The Kendall County Sheriff’s Office alone responded to more than 200 mental health-related calls in 2021, and nearly 20% of inmates in the county jail are on mental health medications, with 16% taking more than one, according to data posted on the department’s website.

Boddie also provided data showing that in 2023, Boerne and Kendall County had a total of 113 suicide attempts or threats and nine deaths by suicide.

“Juvenile emergency detentions, suicide attempts that have been reported to us, death by suicide, juvenile suicidal outcries by the school district… all of those numbers are increasing, every one of them,” Boddie said. “I know our population is increasing, but if you look at the rate that they’re increasing by, our death by suicide is above the national average per capita. That’s scary that that’s happening.”

Mental health officers in Kendall County

The purpose of the mental health deputy program is to divert individuals in behavioral crises from hospitals and jails to community- based treatment options, according to Texas Health and Human Services, which administers the state program.

Mental health deputies or officers receive specialized crisis intervention training from the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement. This training is separate from the 40-hour statewide education and training program on de-escalation and crisis intervention mandated by the Sandra Bland Act of 2017 for all peace officers.

In Boerne, Mental Health Officer Rebecca Foley responds to patrol officers’ calls about potential mental health crises and follows up with people in crisis to ensure they are getting the mental health help that they require.

Foley has been in the mental health officer position for three years, and she said it started after the Boerne Police Department noticed an increase in emergency detentions. She has a degree in criminal justice and a second degree in mental health counseling, but she said that type of background is not required.

“You actually have to have the right person to be in this position,” Foley said. “You have to have empathy. You have to have a heart.”

The Texas Commission on Law Enforcement (TCOLE) records show that Boerne PD has nine mental health officers, but Foley said she is the only one working in that capacity for now, although the department is working on hiring a second mental health officer.

Kendall County Sheriff ’s Office has two mental health deputies and a Crisis Intervention Team (C.I.T), which their website states “ offers assistance to those suffering from emotional and psychological issues and assists them in obtaining the appropriate social service available for their specific needs.”

Although TCOLE reports that the Fair Oaks Ranch Police Department has six mental health officers, Cpl. Jason Hanley said the department has none. According to Hanley, larger agencies serving bigger populations are more likely to have designated mental health officers.

Hanley said all police officers at Fair Oaks Ranch PD are trained in de- escalation and crisis intervention and can distinguish between a criminal mindset and a mental health crisis.

“Someone who’s in a mental health crisis, they’re not a criminal, they’re not a bad person,” Hanley said. “They’re just having a bad time in life at that point and our goal is to get them help. That is the overall goal.”

Hanley said the department is working to implement an “R-U-OK” program, used by other Texas departments, allowing participants to receive weekly check-in calls about their well-being. If mental health concerns arise, the department would contact family members or provide service referrals.

The mental health crisis

Texas ranks dead last when it comes to access to mental health care in the U.S., according to Mental Health America, a national nonprofit dedicated to the promotion of mental health, well-being and illness prevention.

“ Texas ranks very low in access to mental healthcare overall when you compare it to other states,” said Greg Hansch, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Health in Texas. “Access to mental health care in rural areas is limited… Lack of services and transportation are among the top two barriers that people express when it comes to accessing mental healthcare in rural areas.”

NAMI data also shows that about two in five incarcerated people have a history of mental illness, and more specifically 70% of youth in the juvenile justice system have a diagnosable mental health condition.

“We’ve seen far too many examples of dramatically negative consequences resulting from law enforcement officers being there on the scene, kind of quarterbacking a response to a mental health crisis – people have lost their lives,” Hansch said. “People end up disproportionately incarcerated.”

Mental health of police officers

While Foley serves the Boerne community, she is also working on a new program to provide support to fellow officers struggling with mental health issues. A peer support team is being developed that will allow first responders to reach out to Foley or another team member after a difficult call or during a personal crisis.

“I would say probably at the beginning of the year, we’ll be able to launch that out, but that’s one of the biggest things as far as helping our own people because we don’t always want to ask for help,” Foley said.

In Fair Oaks, Hanley said officers have an employee assistance program, along with healthcare covering mental health. As a supervisor, Hanley also makes sure to check on the welfare of his officers every day and helps them get guidance when needed.

“Obviously, we see the worst things all the time, and whenever we see people, we’re seeing them at the worst possible time,” Hanley said. “Just because you need to go talk to someone, just because you need to get things inside your head squared away and dealt with an appropriate manner does not mean you’re not effective as a police officer... It just means you’re trying to take care of yourself.”

Jamie Moore is a journalism major at Texas State University with a minor in communication studies and a contributor to Texas Community Health News, a collaboration between the School of Journalism and Mass Communication and the university’s Translational Health Research Center. She grew up in Grandview and hopes to work as a journalist in the Austin area.

Comment

Comments