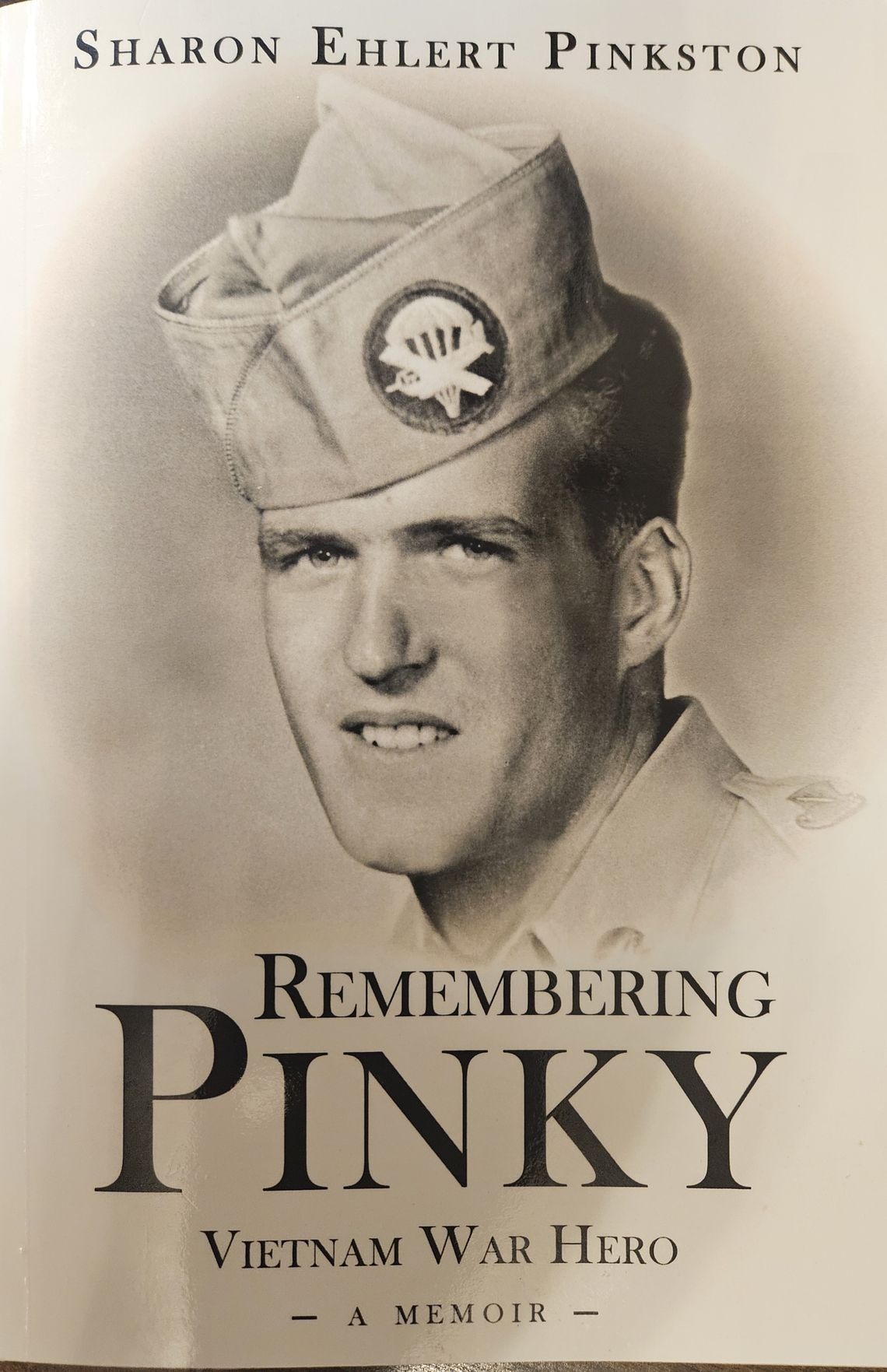

Robert Pinkston was a poor boy born during the Great Depression who enlisted in the Army at a young age “and was enjoying life as a husband and father when he was caught up in the Vietnam War.”

Pinkston never returned, losing his life during the Tet Offensive in 1968. Sharon Pinkston, his widow, sat down and penned “Remembering Pinky, Vietnam War Hero,” which published earlier this year.

Sharon Pinkston shares personal feelings, interaction — happiness, grief, elation, strife — that every spouse experiences during life with a military man or woman.

“It took me awhile before I was ready, because I didn’t want to go back there, mentally,” Pinkston said in describing the challenges in writing the 136page book. “Then I thought, ‘No one is going to remember him once I’m gone.’ That’s why the title is ‘Remembering Pinky.’” Pinkston, a Boerne resident for the past two years after spending two previous decades in Bulverde, tracked the life of her husband Robert Pinkston, who was already enlisted in the Army when they first met.

They met when she was 15, a junior in high school. She and her father moved to the Bloomington, Illinois area where she underwent some surgery for polio.

While there, she befriended the female operator of a pizza parlor. Sharon lost her mother when she was 11, and she said this woman “really filled a void in my life” with her motherly ways.

The woman’s brother-in-law was the quiet, somewhat reserved Robert “Pinky” Pinkston.

“He would come home on leave, already in the military ... and I developed a crush on him,” Sharon said.

Pinkston was shipped off to Germany in the 1950s and the two began corresponding. A romance developed and when he was sent to Fort Ord in Monterrey, California, Sharon traveled out to meet him. Shortly thereafter, the couple married in Reno and began their life together.

The couple spent three years in Monterrey, where her son Tony was born. Then came three years in Alaska, another three-year deployment to Fort Polk, Louisiana.

Pinky’s first Vietnam deployment came in 196566, when Sharon spent time in Golden, Colorado, living near her father. A move to Fort Hood in Texas followed Pinky’s return to the states in late 1966, before he was assigned a 90-day TDY in February 1968.

“The first time he was over there, I worried a lot about him,” she said. “He was sent back in February of 1968. He was only (going to be there) for, like 90 days, so I wasn’t quite as worried, because I thought it was such a short time.”

The first 80 pages of “Remembering Pinky” describe their lives stateside: the moves, the car breakdowns, the movies, the PX, the schools and the kids — a military life on military bases for a young couple.

The final 50-some pages contain letters exchanged between Sharon and Pinky once he shipped out to Vietnam in February.

In the book, she recounts the last time she saw him — a “dreary, drizzly day” in February.

On Jan. 30, 1968, North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops launched the Tet Offensive against South Vietnamese and United States targets, and the U.S. responded with a call-up of thousands of troops ... Pinky included.

“As Pinky feared, he received his orders to go TDY to Vietnam for 90 days,” she wrote.

On Feb. 17, the dreaded day finally came.

“I had cried the night before, when we went to bed; Pinky said nothing, but he must have dreaded returning to Vietnam,” the book tells. “We were both thankful that he was only to be gone for 90 days.”

Sharon and their children traveled with Pinky to Fort Hood “and we said our goodbyes ... that dreary, drizzly day was reflective of our moods. Words couldn’t convey the sadness we were all feeling.”

Sharon’s first letter in the book was dated Feb. 19, 1968, warranting a return dated Feb. 22 from Pinky.

The tone of his letters, Sharon writes, “didn’t convey the danger surrounding him and his unit.”

Camp Coryell, in Ban Me Thout in Vietnam, was subjected to repeated enemy 82mm mortar attacks.

Chapter 11, titled “The Last Letters,” contains final correspondence between Sharon and her husband. “Pinky never received the following letters. They were returned to me unopened,” the chapter starts.

The last letter she received from her husband was dated March 13, 1968. In it, he tells of receiving her March 4 and 5 letters, mentions a fellow soldier he had befriended, and tells her to hold off buying a mower until he gets home.

He then signs off, “Honey, it is now 2200 (10 p.m.) and I have to go out and inspect my guards, to make sure they are awake, at least one of them anyway,” Pinky writes.

It’s the last letter he’ll ever write. Pinky died that night.

His commanding officer, in his report of activities that night, wrote: “On 13 March at 2220 hours, (10:20 p.m.) the 155th AHC compound was again attacked by a hostile force employing 82mm mortars.

“Pinky was attempting to extinguish a fire on the miniport or refueling facility when he was struck by enemy fire. He was immediately given medical attention and a medical evacuation undertaken. Enroute to the 91st Evacuation Hospital ... he passed away.”

Just 20 minutes after he signed off “I miss all of you and the kids,” Pinky lost his life serving his country.

Sharon describes the 6:15 a.m. visit from a warrant officer, who arrived to tell her that her husband was missing in action — “the biggest shock of my life.”

“What I later heard was they had so many bodies, they were slow in identifying people,” Sharon said of his initial “missing in action” declaration.

“In his first letters to me, it didn’t sound like it was all that bad there.

“All that time, in writing the book, I thought, ‘There was probably a lot that he was really scared about, and nervous about, that he didn’t convey to me,” she said. “He never talked about fears or worries, anything like that. He was pretty reserved ... and he just soldiered on, as so many of them did.”

Pinky’s story, unique to Sharon and its readers, encapsulates the story of so many who fought in Vietnam — any war, actually — and lost their lives. 58,000 men and women died serving in Vietnam. Pinky’s story is just one of the 58,000 to be told, so others can one day grab the book and spend time “Remembering Pinky.”

Comment

Comments