Editor’s note: Second of a two-part series chronicling the history of Kendall County and its namesake, George Wilkins Kendall. Everything included in this story was taken from Bryden Moon’s March 5 presentation at the Patrick Heath Public Library.

Kendall County Historical Commission member Bryden Moon said in order to talk about George Wilkins Kendall, the namesake of Kendall County, the clock needs to be rolled back to 1809.

Kendall was born on August 22 of that year in Mont Vernon, New Hampshire, and was the first of five children of Thaddeus and Abigail Wilkins Kendall.

Times were hard, Moon said, and Thaddeus moved his family from one settlement to another. At the age of 7, George visited his grandfather and wound up living with him.

“George learned to read, and when it was a topic that interested him, he would devour it,” Moon said during his presentation to guests who attended his Kendall of Kendall lecture on March 5 at the Patrick Heath Public Library. “Geography was his favorite subject. He looked at dogeared books and well-worn maps, and dreamed.

“He longed to visit farflung places. Young Kendall wanted to travel and desired to live a life of action and adventure.”

He remained under his grandfather’s roof for 10 years.

Moon said at age 15 he announced to his family he wanted to be a printer, and at age 16 he was in Boston, Massachusetts, living with his uncle and working as a printer’s apprentice.

Road of adventure

At 17, Kendall started his road of adventure. Traveling on his own, he went to New York but had trouble finding a printing-related job. So, he explored the Midwest and the Southeast.

By his 26th birthday in 1835, Wilkins had been in at least 14 states and the terri tory of Wisconsin. In 1835, there were only 24 states.

After arriving in New Orleans, Louisiana, Moon said Kendall in 1837 co-founded the Picayune newspaper with F.A. Lumsden in 1837.

“Much of the news flowed south with Mississippi River on incoming boats,” Moon said. “So in a classic Kendall move, in order to out-hustle the competing newspapers, he would take a small printing press and board a boat that was going north on the Mississippi River.

“Then while returning home, Kendall would interview folks and use the small press to print up the news. Upon reaching New Orleans, he would walk off the ship with printed news and beat the competition.” Kendall was involved with the Picayune newspaper the rest of his life, and the newspaper still is printed today.

Moon then moved ahead to the 1841 Santa Fe expedition.

“The Texan Santa Fe Expedition, a political-military-commercial venture, was occasioned by Republic of Texas President (Mirabeau) Lamar’s desire to divert to Texas at least a part of the trade then carried over the Santa Fe Trail,” he said. “Texas needed trade, and the Santa Fe market apparently offered the best opportunities.

“Kendall always had wanted to take a journey of exploration, and the Republic of Texas was happy to have him. Who better than the editor of New Orleans Picayune to chronicle this adventure to and through the outer edges of civilization into the West?”

While in Austin waiting for the expedition to get underway, Kendall experienced two significant events, Moon said.

First, he joined a prearranged side trip to San Antonio.

“This was Kendall’s first trip to San Antonio, but it was not the city that captured his imagination,” Moon said. “It was on this side trip that he discovered the Hill Country. He was impressed with the clear, cool streams, the wide valleys and the drier climate and gentle breezes. For Kendall, this was the ideal landscape and … he never forgot the natural beauty of the Hill Country.”

The second significant event, after returning to Austin before the expedition left, Kendall decided to take a swim one evening in the Colorado River. But it was dark and he missed his normal path and fell many feet over a cliff onto a boulder and broke his ankle. He worried he would not be able to go on the expedition because he could not walk, but Lamar visited his bedside, and shortly thereafter Kendall received confirmation that a special wagon would be provided to carry him.

Santa Fe expedition

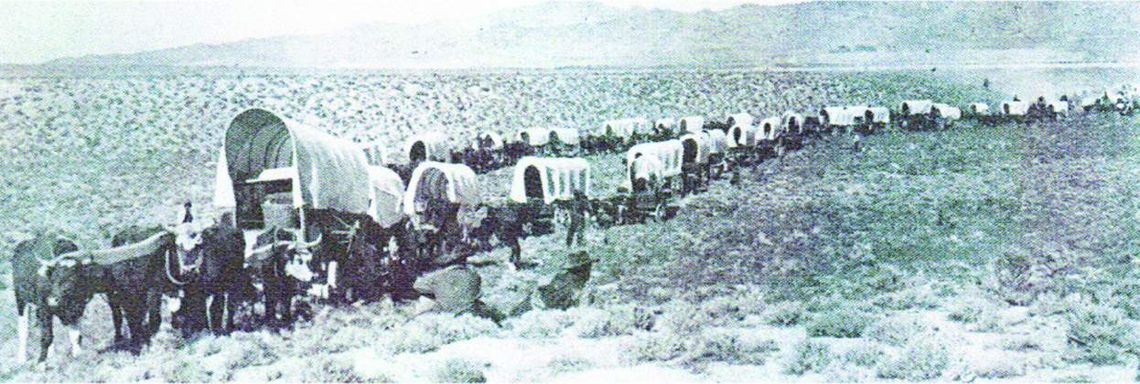

“The Republic of Texas launched this expedition on June 19, 1841,” Moon said. “Traders with wagonloads of merchandise, accompanied by a military escort as protection against the Indians, would cross the plains to exchange their goods for bullion and furs. There were 24 wagons in all, over 300 participants, including many soldiers.”

Moon said the goal was to travel through the wilds of Texas to the capital of New Mexico, Santa Fe, but there was no road.

“And they did not know it at the time but they had miscalculated several things, including underestimating the distance they would travel by nearly half,” he said.

Finally, after three months of traveling, when Kendall’s expedition party arrived at New Mexico on September 16 they were not greeted but arrested.

“The Texans had expected to be welcomed by the citizens of New Mexico and certainly had not anticipated armed resistance, but the governor of New Mexico had learned of the expedition and had detachments out awaiting the arrival of the Texans,” Moon said. “Most of the party had survived the journey to New Mexico, but now they were imprisoned.”

On Oct. 17, a forced 2,000-mile march to Mexico City began. It was on foot. Kendall was now walking on an ankle that had been broken just four months before, Moon said.

After Christmas, outside of Mexico City, Kendall’s party stopped marching and all were placed in jail. They had traveled the 2,000 miles in a little over two months.

“Kendall remained jailed until influential friends secured his release in May 1842 after spending seven months in captivity,” Moon said, adding on his return to New Orleans he ran a serial account of the expedition in the Picayune. Starting on June 17, 1841, the Picayune published 23 of Kendall’s letters detailing his experience.

In 1844, he published the “Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition,” a 900-page two volume book.

War with Mexico

Moon continued as he moved ahead to 1846.

“Hermann Spiess was the Adelsverein’s third commissioner general. In early 1846, before his association with Adelsverein, he relates an unscheduled venture to a Plains Indian Treaty. “Guess who his host is?”

“Guess who his host is?” Moon said. “’… Kendall was so kind as to invite me along. Four Rangers went along … arrived at the treaty place where numerous tribes and Indian nations were represented. I was there for a week when the news arrived in our camp of war with Mexico having broken out at the Rio Grande. Kendall immediately set out for the theatre of war. …’ So, here is Kendall covering one adventure for the Picayune, headed out to another adventure of a lifetime.”

Kendall was back in the limelight. Between 1846 and 1848, Mexico and the United States waged war over Texas and the Mexican lands of western North America.

“This turn of events once again put Kendall in the spotlight as he headed to the Texas-Mexican border to cover the unfolding war front for the Picayune,” Moon said. “He entered Mexico with the U.S. Army to see first-hand what was going on, and due to his knack for writing and his persistence in getting the details to the presses first, Kendall became known as the first modern war correspondent and most widely known reporter in America in his day.”

In advance of these battles, Moon said Kendall set up riders and routes to ports. The riders would then rush his letters, notes and dispatches regarding active battles to the boats on the Mexican coast and then ship them to the Picayune office in New Orleans and again beat the competing newspapers with the latest news on the war.

The war ended in 1848 with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Mexico recognized the Rio Grande as the border of Texas and signed over all of California, Utah and Nevada as well as parts of New Mexico, Arizona, Wyoming and Colorado.

The Hill Country

After the Mexican War, Moon said Kendall took a boat to Europe for what was meant to be a short vacation and to write a book on the Mexican War, but he postponed writing the book to cover the unfolding events in Europe as in 1848 many countries were undergoing revolts against rulers and monarchies.

“In France, Kendall met his future wife, Adeline,” Moon said. “They married in 1849 and he wound up staying in Europe for two years. …

“In 1850, Kendall returned to the United States to work on publishing and promoting his book, “The War between the United States and Mexico, Illustrated.”

He traveled back and forth between the U.S. and Europe, still writing articles for the Picayune.

Moon said it was during this window of time Kendall focused on securing land for his next enterprise, raising sheep in the Hill Country land that had “enchanted” him 11 years earlier.

“In late 1852 while visiting, he describes New Braunfels to his wife as ‘the great German settlement,’” he said. “Later, flushed with pride about finding his ideal home site, he writes about ‘a pleasant and verdant valley, surrounded on all sides by rough, rocky and rugged mountains’ with ‘rich grass’ and a ‘beautiful stream’ located about 6 miles northwest of New Braunfels. …

“In 1854 we learn that Kendall has also started a satellite ranch on the 4,000-plus acre Ortiz Survey. Located just a few miles east of Boerne, Kendall called it Post Oak Spring Ranch. Much larger than his New Braunfels operation, he now dreamed that this would be the future site of a great ranching establishment.” However, one reason for

However, one reason for not building there immediately was the fear of Indians.

“Kendall made many trips to Post Oak Spring Ranch, always alert for any sign of Indians, writing in 1856: ‘Today I am not certain that my shepherds have not been killed and scalped, and my flocks scattered,’” Moon said in quoting Kendall. “’Within the last month or two the Indians have been on every side of me: my great good fortune has so far been that the rascals do not seem to have contracted a taste for mutton.’”

In later years, Kendall kept a diary. The entries from 1857 attest to frequent trips to his satellite ranch.

Moon continued by saying Kendall constantly was bombarded with letters about Texas – all facets – and it is said he took the time to answer each, despite the fact that at this time he had two ranches, four large flocks of sheep, a grist mill and a stock of horses and cattle to look after and a newspaper to write for. To deal with these demands, in 1858 he sat down and poured all of his enthusiasm for Texas into a 3,600-word letter and sent it off to the Picayune to be printed into circulars. When his bundle of these circulars came from New Orleans, the task of letter writing was simpler. He either mailed a copy to each distant inquirer or sent one along with a hasty note.

“Regionally, Kendall’s stature and legend grew,” Moon said. “… About this same time due to his storied reputation, his promotion of Texas and the Hill Country and his continued highly successful sheep-ranching enterprise, Kendall is touted as a candidate for governor. In 1859, several newspapers, and the German residents of both Boerne and New Braunfels launched a campaign to elect him governor.

“Kendall is genuinely not interested and writes to the San Antonio Herald, ‘I have no taste for the calling of a politician, have never been in the business, and am too old to learn a new trade,’” Moon said.

By 1858, Kendall had moved his entire family from France to his ranch outside of New Braunfels. Kendall is available for the December 1859 petition to form a new county.

Kendall County

In February 1861, he and his family take up residence at Post Oak Spring Ranch. Less than one a year after the move, Kendall County is created on January 10, 1862.

The first Kendall County tax records show he has amassed 6,000 acres in the new county, worth over $42,000.

“Earlier I mentioned that when casting about for a new county name, it is easy to see how George Wilkins Kendall’s name would have been placed at the top of a short list as Kendall was so well respected that his name would have been placed at the top of any list,” Moon said. “That was certainly the case on the 1859 petition, and that is literally what you find when going through the Kendall County Commissioners Court minutes.”

Moon added that Kendall was a participating member of his new county, and the Kendall County commissioners put him to work as he was selected as a grand juror on May 18, 1863, as well as one of a three-member board of school examiners.

“George Wilkins Kendall rolled up his sleeves during his time in Kendall County, experiencing the ups and downs of working the lands through droughts, floods, locusts, wolf attacks, Native American attacks, through loss of animals, loss of employees and loss of lives, through northers and intense heat,” Moon said. “He quietly died at his ranch of ‘congestive chills’ on October 21, 1867, at the age of 58.”

Kendall was buried in the Boerne Cemetery. His is the only Boerne gravesite with a Texas Historical Commission marker.

Moon said Post Oak Spring Ranch over time has been carved into many lots and ranches.

“Yet you do not need permission to traverse Post Oak Springs Ranch, and you have already done so many times,” he said. “Every time you travel along State Highway 46 East to and from Boerne, 3 miles of your route cuts a diagonal through the heart of George Wilkins Kendall’s final homestead.

Moon gave much of the credit for his presentation to Fayette Copeland’s book, “Kendall of the Picayune,” which was published in 1943.

Comment

Comments